The Characteristics of High-Frequency Trading Systems

In the current financial markets, there is a significant need for high-frequency trading (HFT) systems. Java, renowned for its cross-platform compatibility, efficient development capabilities, and maintainable features, is extensively employed within the financial industry. High-frequency trading revolves around the rapid execution of buy and sell transactions, leveraging swift algorithms and advanced computer technology, all while prioritizing the attainment of low-latency targets.

The Challenges: High Concurrency Processing and Low Latency Requirements

High-frequency trading systems necessitate managing many trade requests within extremely tight timeframes, creating substantial demands for robust concurrency processing capabilities and exceptional low-latency performance.

How can the challenges of high concurrency and low latency be tackled?

Conventional data structures and algorithms may be inadequate to meet high-frequency trading systems’ high concurrency and low latency demands. As a result, exploring more efficient concurrent data structures becomes imperative.

Limitations of Traditional Queues in High-Frequency Trading Systems

Traditional queue data structures, such as LinkedList, ArrayBlockingQueue, and ConcurrentLinkedQueue, face limitations in high-frequency trading systems. These queues may encounter issues like lock contention, thread scheduling overhead, and increased latency, preventing them from meeting high-frequency trading requirements. The lock and synchronization mechanisms in traditional queues introduce additional overhead, restricting their ability to efficiently handle high concurrency and achieve low-latency performance.

The limitations of traditional queues in high-frequency trading systems can be summarized as follows:

- Lock contention: Traditional queues use locks to ensure thread safety during concurrent access. However, when many threads compete for locks simultaneously, performance can degrade, and latency can increase. Locks introduce extra overhead, potentially leading to thread blocking and extended system response times.

- Thread scheduling overhead: In traditional queues, frequent thread scheduling operations occur when threads wait or are awakened within the queue. This overhead adds to system costs and introduces additional latency. Frequent thread context switching in high-concurrency scenarios can waste system resources and degrade performance.

- Increased latency: Due to issues like lock contention and thread scheduling, traditional queues may fail to meet the low-latency requirements of high-frequency trading systems in high-concurrency environments. Trade requests waiting in the queue experience increased processing time, resulting in longer trade execution times and affecting real-time responsiveness and system performance.

These limitations prevent the standard queues provided by the JDK from meeting the high concurrency processing and low-latency performance requirements of high-frequency trading systems. To address these issues, it is necessary to explore more efficient concurrent data structures, such as the Disruptor, to overcome the challenges posed by high-frequency trading systems.

Introduction to the Disruptor Framework

Disruptor is a high-performance concurrent data structure developed by LMAX Exchange. It aims to provide a solution with high throughput, low latency, and scalability to address concurrency processing challenges in high-frequency trading systems.

Core Concepts and Features of Disruptor

Disruptor tackles concurrent challenges through core concepts such as the ring buffer, producer-consumer model, and lock-free design. Its notable features include:

- High Performance: Disruptor’s lock-free design minimizes competition and overhead among threads, resulting in exceptional performance.

- Low Latency: Leveraging the ring buffer and batch processing mechanism, Disruptor achieves extremely low latency, meeting the stringent requirements of high-frequency trading systems.

- Scalability: Disruptor’s design allows effortless expansion to accommodate multiple producers and consumers while maintaining excellent scalability.

Ring Buffer

The Ring Buffer is a core component of the Disruptor framework. It is a circular buffer for efficient storage and transfer of events or messages, enabling high-performance and low-latency data exchange between producers and consumers.

Key Features of Disruptor’s Ring Buffer:

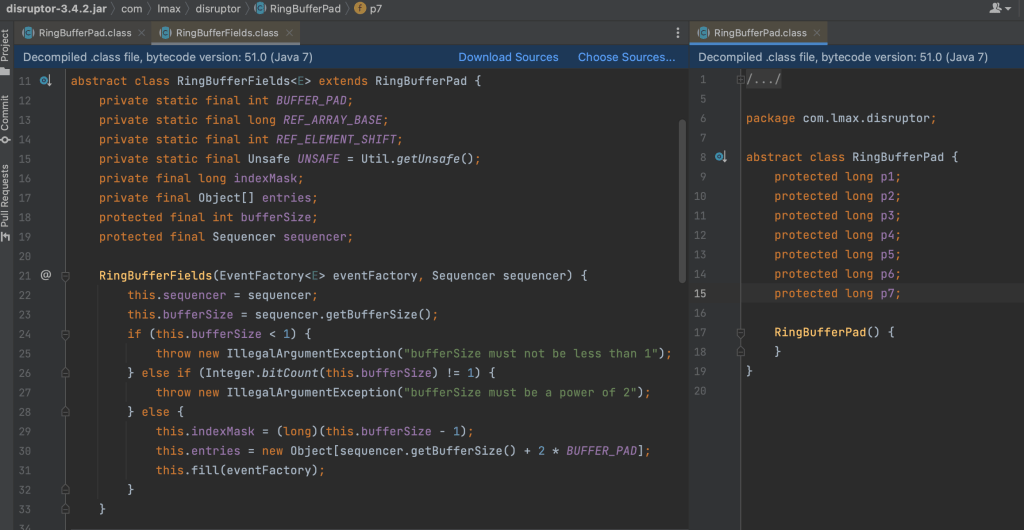

Cache Line Optimization

Disruptor is designed to leverage cache line utilization for improved access efficiency. By placing padding data in the same cache line, unnecessary cache contention and cache invalidation are minimized, resulting in enhanced read and write performance.

The following code demonstrates how to improve performance by using padding data placement.

import java.util.concurrent.CountDownLatch;

public class CacheLinePadding {

public static volatile long COUNT = 10_0000_0000L;

private static abstract class TestObject {

public long x;

}

private static class Padded extends TestObject {

public volatile long p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7;

public long x;

public volatile long p9, p10, p11, p12, p13, p14, p15;

}

private static class Unpadded extends TestObject {

// Empty class, no padding required

}

public static void runTest(boolean usePadding) throws InterruptedException {

TestObject[] arr = new TestObject[2];

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(2);

if (usePadding) {

arr[0] = new Padded();

arr[1] = new Padded();

} else {

arr[0] = new Unpadded();

arr[1] = new Unpadded();

}

Thread t1 = new Thread(() -> {

for (long i = 0; i < COUNT; i++) {

arr[0].x = i;

}

latch.countDown();

});

Thread t2 = new Thread(() -> {

for (long i = 0; i < COUNT; i++) {

arr[1].x = i;

}

latch.countDown();

});

long start = System.nanoTime();

t1.start();

t2.start();

latch.await();

System.out.println((usePadding ? "Test with padding: " : "Test without padding: ") +

(System.nanoTime() - start) / 100_0000);

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

runTest(true); // Test with padding

runTest(false); // Test without padding

}

}

Here’s the result:

Test with padding: 738

Test without padding: 2276Similar Implementation in the Disruptor Framework

Circular Buffer Structure

Disruptor utilizes a circular buffer as its primary data structure, providing efficient event storage and delivery. Using a circular buffer eliminates the need for dynamic memory allocation and resizing, optimizing overall performance.

Strict Ordering

Disruptor ensures events are consumed in the same order they were produced, maintaining data flow integrity and consistency.

Lock-Free Design and CAS Operations

Disruptor employs a lock-free design and atomic operations, such as Compare-and-Swap (CAS), to achieve high concurrency. This reduces thread contention and enhances concurrent processing capabilities.

For a detailed understanding of how CAS (Compare and Swap) operates and its application in addressing high concurrency challenges, I recommend referring to my previous article available at: https://masteranyfield.com/2023/07/03/unleashing-the-potential-of-synchronized-and-cas-addressing-high-concurrency-challenges-in-e-commerce-and-hft/.

High Performance and Low Latency

By leveraging the circular buffer and batch processing mechanisms, Disruptor achieves exceptional performance and ultra-low latency. It meets the stringent low-latency requirements of high-frequency trading systems.

Scalability

Disruptor’s design allows for easy scalability to accommodate multiple producers and consumers, providing flexibility to handle increasing thread and processing demands.

Disruptor VS Traditional Queues

Disruptor offers significant advantages over standard JDK queues in terms of low latency, scalability, and high throughput:

- Low Latency: Disruptor is designed to achieve low-latency data processing. By minimizing lock contention, reducing thread context switching, and leveraging the ring buffer structure, Disruptor provides extremely low event processing latency. This makes it highly suitable for applications with strict real-time requirements, such as high-frequency trading systems.

- Scalability: Disruptor employs a lock-free design and efficient concurrent algorithms, allowing it to effortlessly scale to accommodate multiple producers and consumers. This enables Disruptor to handle large-scale concurrent operations while maintaining high performance and scalability.

- High Throughput: Disruptor achieves exceptional throughput through optimized design and lock-free mechanisms. Multiple producers and consumers can operate in parallel by utilizing the ring buffer and implementing batch processing, maximizing system throughput.

Disruptor is well-suited for scenarios with high concurrency and demanding low latency, while traditional queues are suitable for general concurrency requirements.

Comparing Disruptor Performance with LinkedBlockingQueue and ArrayBlockingQueue

import com.lmax.disruptor.*;

import com.lmax.disruptor.dsl.Disruptor;

import com.lmax.disruptor.dsl.ProducerType;

import java.util.concurrent.*;

/**

* Author: Adrian LIU

* Date: 2020-07-18

* Desc: Compare the difference of performance between Disruptor, LinkedBlockingQueue and ArrayBlockingQueue

* implemented Producer and Consumer with single producer and consumer

* Disruptor took 137ms to handle 10000000 tasks

* ArrayBlockingQueue took 2113ms to handle 10000000 tasks

* LinkedBlockingQueue took 1312ms to handle 10000000 tasks

*/

public class DisruptorVSBlockingQueueWithSingleProducerConsumer {

private static final int NUM_OF_PRODUCERS = 1;

private static final int NUM_OF_CONSUMERS = 1;

private static final int NUM_OF_TASKS = 10000000;

private static final int BUFFER_SIZE = 1024 * 1024;

public static void main(String[] args) {

LongEventFactory factory = new LongEventFactory();

ExecutorService service1 = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

SimpleTimeCounter disruptorTimeCount = new SimpleTimeCounter("Disruptor", NUM_OF_PRODUCERS + 1, NUM_OF_TASKS);

Disruptor<LongEvent> disruptor = new Disruptor<LongEvent>(factory, BUFFER_SIZE, service1, ProducerType.SINGLE, new SleepingWaitStrategy());

LongEventHandler handler = new LongEventHandler(NUM_OF_TASKS, disruptorTimeCount);

disruptor.handleEventsWith(handler);

disruptor.start();

RingBuffer<LongEvent> ringBuffer = disruptor.getRingBuffer();

LongEventTranslator translator = new LongEventTranslator();

disruptorTimeCount.start();

new Thread(() -> {

for (long i = 0; i < NUM_OF_TASKS; i++) {

ringBuffer.publishEvent(translator, i);

}

disruptorTimeCount.count();

}).start();

disruptorTimeCount.waitForTasksCompletion();

disruptorTimeCount.timeConsumption();

disruptor.shutdown();

disruptor.shutdown();

service1.shutdown();

SimpleTimeCounter arrayQueueTimeCount = new SimpleTimeCounter("ArrayBlockingQueue", NUM_OF_CONSUMERS, NUM_OF_TASKS);

BlockingQueue<LongEvent> arrayBlockingQueue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(BUFFER_SIZE);

LongEvent poisonPill = new LongEvent(-1L);

LongEventProductionStrategy productionStrategy = new LongEventProductionStrategy(0, NUM_OF_TASKS, poisonPill, NUM_OF_CONSUMERS);

LongEventConsumptionStrategy consumptionStrategy = new LongEventConsumptionStrategy(poisonPill, arrayQueueTimeCount);

Thread t1 = new Thread(new BlockingQueueProducer<>(arrayBlockingQueue, productionStrategy));

Thread t2 = new Thread(new BlockingQueueConsumer<>(arrayBlockingQueue, consumptionStrategy));

t2.start();

arrayQueueTimeCount.start();

t1.start();

arrayQueueTimeCount.waitForTasksCompletion();

arrayQueueTimeCount.timeConsumption();

SimpleTimeCounter linkedQueueTimeCount = new SimpleTimeCounter("LinkedBlockingQueue", NUM_OF_CONSUMERS, NUM_OF_TASKS);

BlockingQueue<LongEvent> linkedBlockingQueue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>();

try {

t1.join();

t2.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

consumptionStrategy = new LongEventConsumptionStrategy(poisonPill, linkedQueueTimeCount);

t1 = new Thread(new BlockingQueueProducer<>(linkedBlockingQueue, productionStrategy));

t2 = new Thread(new BlockingQueueConsumer<>(linkedBlockingQueue, consumptionStrategy));

t2.start();

linkedQueueTimeCount.start();

t1.start();

linkedQueueTimeCount.waitForTasksCompletion();

linkedQueueTimeCount.timeConsumption();

}

}

Disruptor took 137ms to handle 10000000 tasks

ArrayBlockingQueue took 2113ms to handle 10000000 tasks

LinkedBlockingQueue took 1312ms to handle 10000000 tasks

Based on our experiments and explanations above, it is evident that Disruptor exhibits significant advantages over the standard JDK Queue in certain scenarios. Its features, such as low latency, high throughput, concurrency, and scalability, effectively address challenges encountered in high-frequency trading (HFT) and other demanding environments.

Here are some of its applications in Fintech and trading systems:

- Trade Data Aggregation: Disruptor’s high throughput and low latency make it ideal for rapidly aggregating and processing large volumes of trade data. It efficiently handles numerous trade requests and ensures real-time and accurate processing.

- Event-Driven Trade Execution: With an event-driven model, Disruptor enables efficient concurrent processing by allowing producers to publishing trade events and consumers to execute the corresponding trade logic. This eliminates performance bottlenecks associated with traditional lock mechanisms, enabling swift trade execution and prompt response to market changes.

- Parallel Computing and Risk Management: Disruptor’s scalability and concurrent processing capabilities facilitate efficient handling of large-scale computing tasks and effective risk management in high-frequency trading. By leveraging Disruptor’s parallel computing capabilities, accurate risk assessment and trade decision execution can be achieved.

- Lock-Free Design and Low Latency: Disruptor’s lock-free design minimizes lock contention and thread scheduling overhead, resulting in low-latency data exchange and processing. This meets the high-concurrency and low-latency requirements of HFT, enabling rapid response to market changes and improved trade execution efficiency.

Summary

Disruptor’s exceptional features, including low latency, high throughput, concurrency, and scalability, empower HFT systems to overcome challenges and achieve faster and more efficient trade execution. Its applications in trade data aggregation, event-driven trade execution, parallel computing, risk management, and lock-free design contribute to its effectiveness in high-frequency trading systems.